- Scientists discovered a huge colony of sea sponges atop a deep-sea mountain in the Arctic Ocean.

- The sponges, which average 300 years old, are thriving by digesting fossilized worms.

- It's the latest discovery in the uncharted, ice-encrusted waters of Earth's polar oceans.

Deep beneath the ice-encrusted Arctic seas near the North Pole, atop an inactive deep-sea volcano, a community of sea sponges has survived for centuries by eating the fossils of ancient extinct worms.

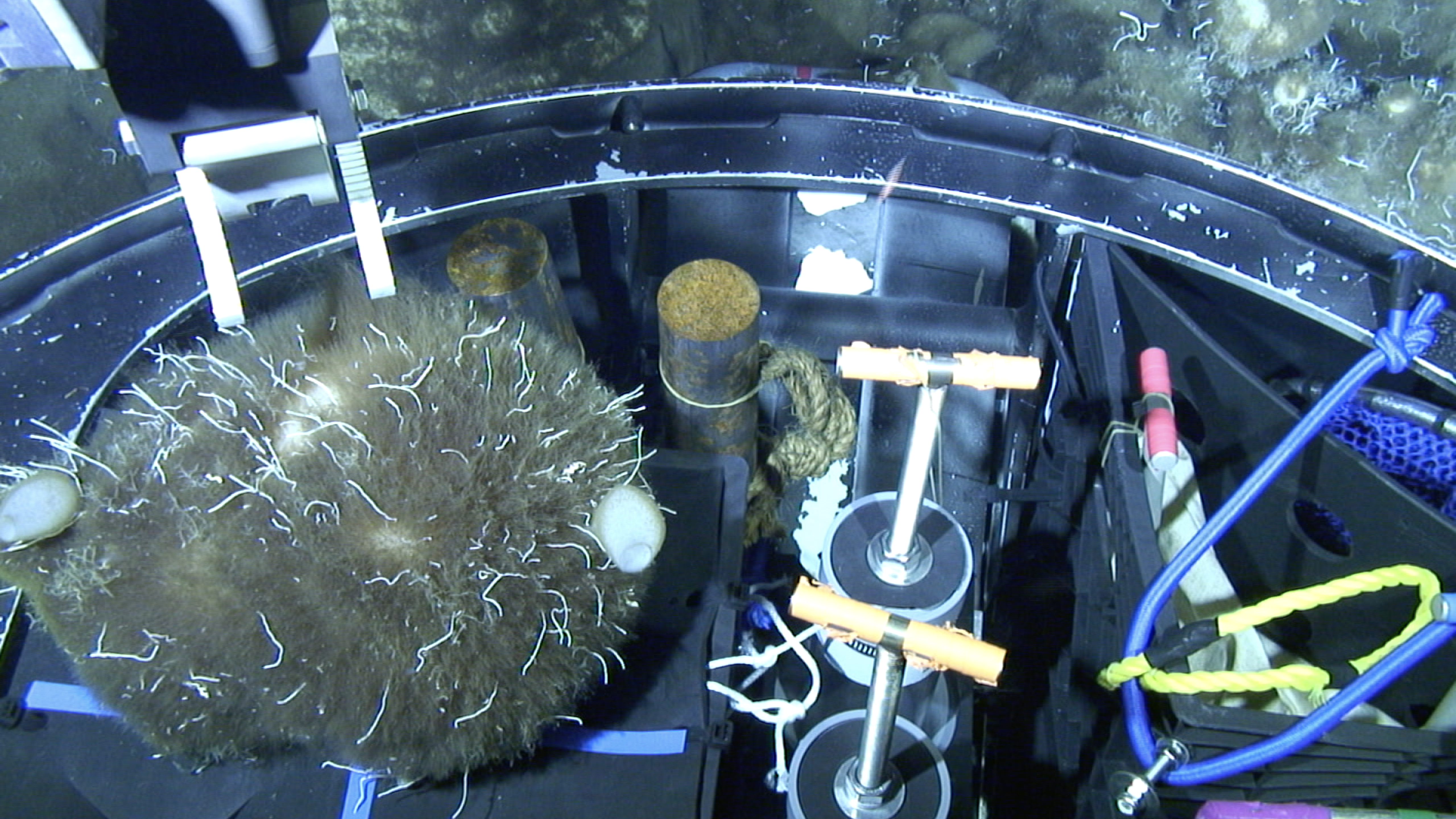

Researchers discovered the underwater mountain in 2011, while mapping uncharted Arctic waters along the ocean-bottom Gakkel Ridge. When they sent a camera-laden sled through the ice and down to the mountaintop, the scientists were surprised to find it crawling with thousands of large, round, squishy, featureless animals covered in hair-like bristles.

"We saw no sea floor. We only saw life. There was one sponge on top of the other, and they were huge," Antje Boetius, a deep-sea biologist at the Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, who led the research, told Insider.

As Boetius's team studied the sponges, they learned strange details about them. On average, the sponges on this mountain are 300 years old. Some of them are slowly moving, which surprised the scientists because nobody had ever documented wild sponges traveling. Boetius and her colleagues could see the tracks where the creatures had crawled uphill.

But one question remained: What were the sponges eating?

On many deep-sea mountains, ocean currents carry nutrients that rain down on the mountaintop and feed the organisms living there. But on this mountain, the scientists' measurements turned up no such nutrients, and no other food sources.

It was a mystery, Boetius said: "In the middle of nowhere, close to North Pole, in the most nutrient-poor environment on Earth, why do we have the largest accumulation of sponges that was ever recorded in the deep sea?"

After about five years of expeditions to Gakkel Ridge, the researchers determined that these sponges are thriving in inhospitable waters by digesting the fossilized remains of a vast community of extinct worms. Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications on Tuesday.

The study follows another polar-ocean discovery that Boetius's colleagues at the Helmholtz Center announced in January: a nest of 60 million icefish breeding in an Antarctic sea.

"To me, this just means we just don't know enough about the oceans," Boetius said, adding, "I sometimes call it a foreign planet on planet Earth, because it's so full of unknown life."

Clues on the ocean floor helped solve a Sherlock Holmes-style riddle

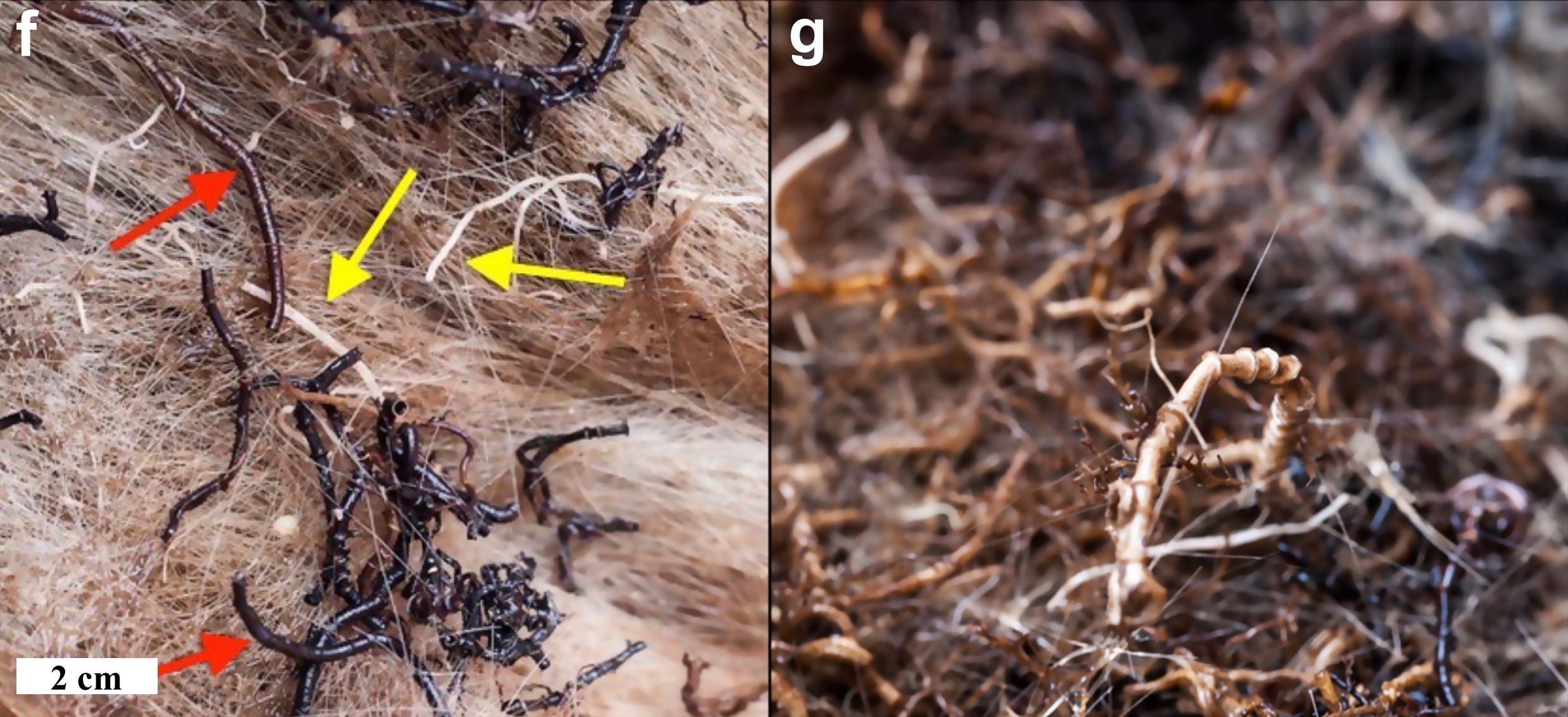

As the scientists scanned the mountaintop for signs of sponge food, they saw crispy black strings everywhere. The material formed thick mats in some places.

Boetius remembered that deep-sea volcanoes often vent gasses like methane and sulfur, which can be converted into energy — a crucial resource in a place devoid of sunlight. She had previously studied deep-sea methane vents, and among the most common forms of life around those vents were tube worms.

With further testing, the researchers determined that the black strings covering the mountaintop were the remnants of ancient tube worms — and many of the tubes were emptied out.

Perhaps the mysteries of the disappearing worm fossils and the missing food source were related. The researchers turned to the sponges they'd captured and analyzed the microbes that filled their bodies, since sponges are often more bacteria than sponge.

They discovered the sponges "have enzymes and tools to digest detritus — very old fossilized detritus," Boetius said, adding, "It was all about old, degraded material."

The smoking gun was that the sponges carried the same nitrogen and carbon isotopes as the worm tubes they sat upon.

"It was just a huge, Sherlock Holmes-like detective private-eye project," Boetius said, adding, "We had a riddle to solve, and it took a very long to have all the data together."

The researchers found no signs of methane venting, nor a single living worm.

The volcano is inactive, and the worms died out thousands of years ago, but their remains now feed a thriving community of otherworldly creatures.

Biologists are racing to study ocean ecosystems before they're gone

It's not clear when the sponges will run out of dead worms to eat, but Boetius thinks their numbers will drop drastically once the fossils are gone. A few sponges may survive by eating the occasional algae falling from above or crustacean poop floating past.

Boetius, however, is thinking about more fast-approaching upheavals to ocean ecosystems. She fears that climate change, plastics, and pollution are changing the seas faster than researchers can survey them.

Oceans cover 70% of Earth's surface, and an estimated 80% of those waters remain unmapped and unexplored, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The temperature and acidity of the oceans are rising, and their ecosystems are especially threatened at the Earth's poles, which are warming faster than anywhere else on the planet and rapidly losing sea-ice cover.

Boetius hopes more deep-sea science expeditions like hers will study hard-to-reach ecosystems before they change with the climate.

"I think it is important that the diversity of life on Earth has at least a record, an image, a sample, a name, because they are maybe vanishing or changing," Boetius said.